This article forms part of the Decorative and Applied Arts Encyclopedia, a master reference hub providing a structured overview of design history, materials, movements, and practitioners.

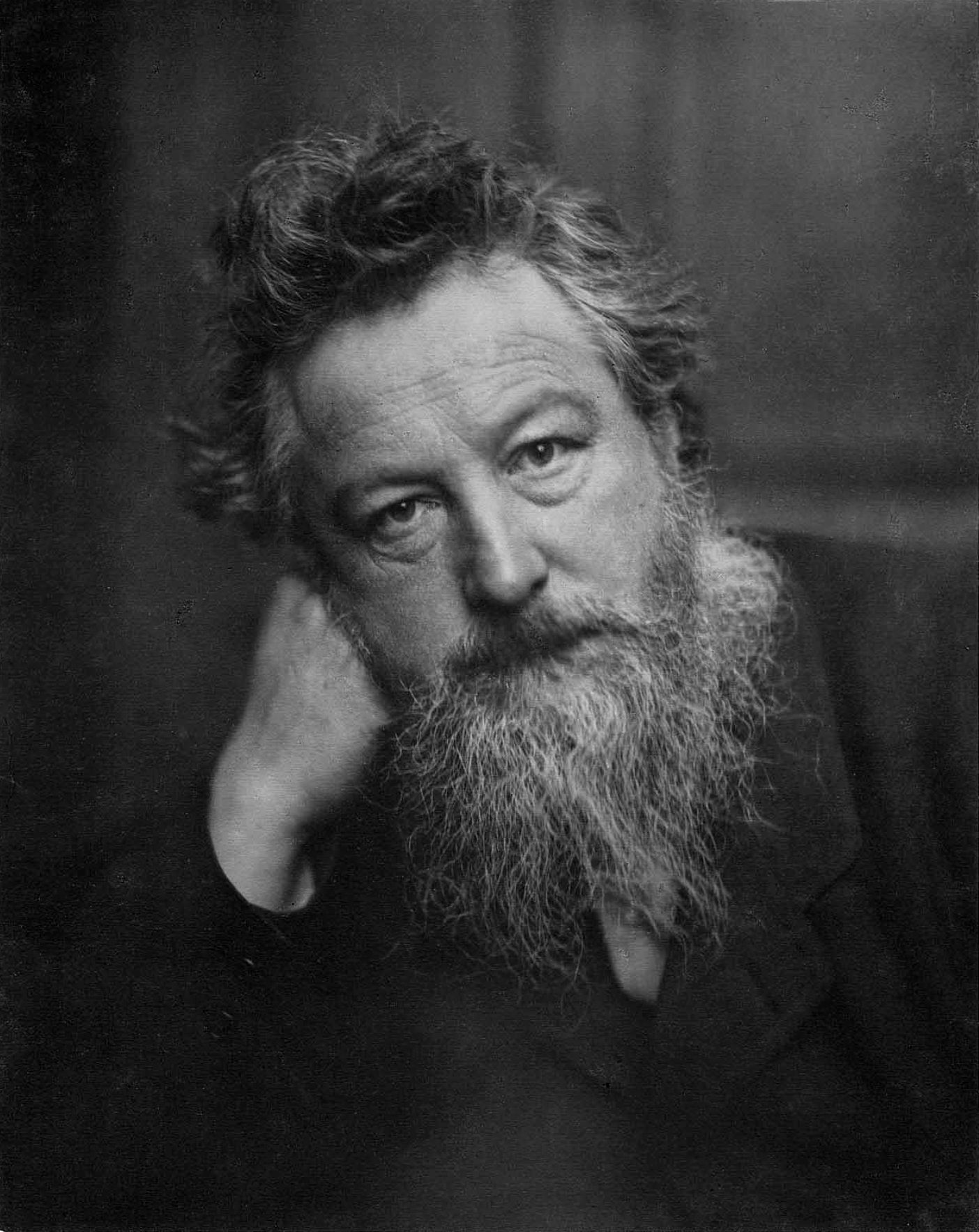

William Morris

Born March 24, 1834

Known for Wallpaper and textile design, fantasy fiction / medievalism, socialism

Notable work Textile and typographic design

“Have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful or beautiful.”

William morris

That was the rallying call of the nineteenth-century designer William Morris, a British designer and social reformer. He aimed to rid the world of shoddy mass-produced goods. He wanted to replace them with objects designed and made by artists.

He has long been regarded as the grand Victorian and is widely regarded as one of the most influential British designers of the nineteenth century.

While at Oxford, he became genuinely interested in the ritual architecture of the Middle Ages. However, his most significant influence came through the readings of John Ruskin. He gradually adopted Ruskin’s ideas on aestheticism and social progress.

Embed from Getty ImagesMorris believed his responsibility was “to revive a sense of beauty in home life, to restore the dignity of art to household decoration.” His designs were much loved by the aesthetic movement of the time, including by Oscar Wilde and Rex Whistler. In 1861, he established his firm to design and produce wallpaper and textiles. Morris made his first printed textile design in 1873. Today, many of his designs remain in use. His original designs remain recoloured and reworked. They are marketed under his name. Other makers used some of his carpet designs.

Art Noveau

William Morris became familiar to Art Nouveau aficionados. His name became as familiar to the general public as those of Picasso and Matisse.

A story is told about Morris that, as a young man on a walking trip in France, he had a vision of a perfect house. So vivid was the image that the 26-year-old scribbled notes describing the property on the only thing he had at hand. This was the back of a French railway timetable.

The home he built in the hamlet of Upton, near Bexleyheath, South East London – known as the Red House — revolutionised British taste.

William Morris – Typography – Kelmscott Press

The Kelmscott Press was the forerunner of the modern printing press. Its influence on present-day print typography is attributable. The typefaces of the Victorian era were ugly, and the notion of ‘visual communication’ was not a significant consideration. Printers lumped an array of different typefaces on the same page. Consequently, the pages became more of an obstacle than a communication aid. There seemed to be an aversion to leaving any white space. Many Rococo embellishments were retained to fill the whitespace.

William Morris articulated his vision in a note on the founding of the Kelmscott Press.

“Letter pure in the form: severe, without needless excrescences; solid without the thickening and the thinning of the line which is the essential fault of the ordinary modern type and which makes it difficult to read; and not compressed laterally as all later type has grown to be owing to commercial exigencies.”

William Morris designed his own typeface based on the fifteenth-century face of Nicholas Jenson. He studied Jenson’s type in great detail. He had it photographed and enlarged, then made drawings of it repeatedly. The resulting type he called “Golden.” In addition to this face, he worked on three others: “Troy” and “Chaucer”.

To contemporary eyes, Morris’s books would perhaps seem rather than the distilled essence of beauty. The pages of his books appear to be close-packed. The type is heavier than would be used today. He also had a weakness for large and ornate capitals. Sometimes they were hand-painted, which gave the page a lopsided appearance.

Embed from Getty ImagesMore British Textile Designers

Marion Mahler: Pioneer of Mid-Century British Textile Design

Marion Mahler, a pioneering textile designer, shaped mid-century modern fabric design in Britain with bold geometric abstractions, leaving a lasting…

Keep readingIlse Crawford for Kasthall: A Harmonious Symphony of Texture and Nature

Ilse Crawford collaborates with Kasthall to create a rug collection inspired by the serene Swedish landscapes, celebrating nature’s beauty and…

Keep readingGeorgina von Etzdorf: A British Design Icon

Georgina von Etzdorf, a British designer, has made a lasting impact in textile, fashion, and product design with her timeless…

Keep readingEileen Hunter (1909 – 1979) British Textile Designer and Writer

British textile designer and writer, Eileen Hunter, revolutionized the industry with her vibrant colors and innovative patterns. Equally skilled in…

Keep readingRobert Yorke Goodden (1909-2002) British Architect Designer

Robert Goodden, a prominent British architect and designer, greatly influenced modern British silver design. He also contributed to post-war design…

Keep readingEvelyn Wyld: Pioneer of British Interior Design

Evelyn Wyld (1882 – 1972) was a British designer who was born in 1882. She studied at the Royal College…

Keep readingDiscover more from Encyclopedia of Design

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.